By Maia Szalavitz

Graphics by Sara Chodosh and Aileen Clarke

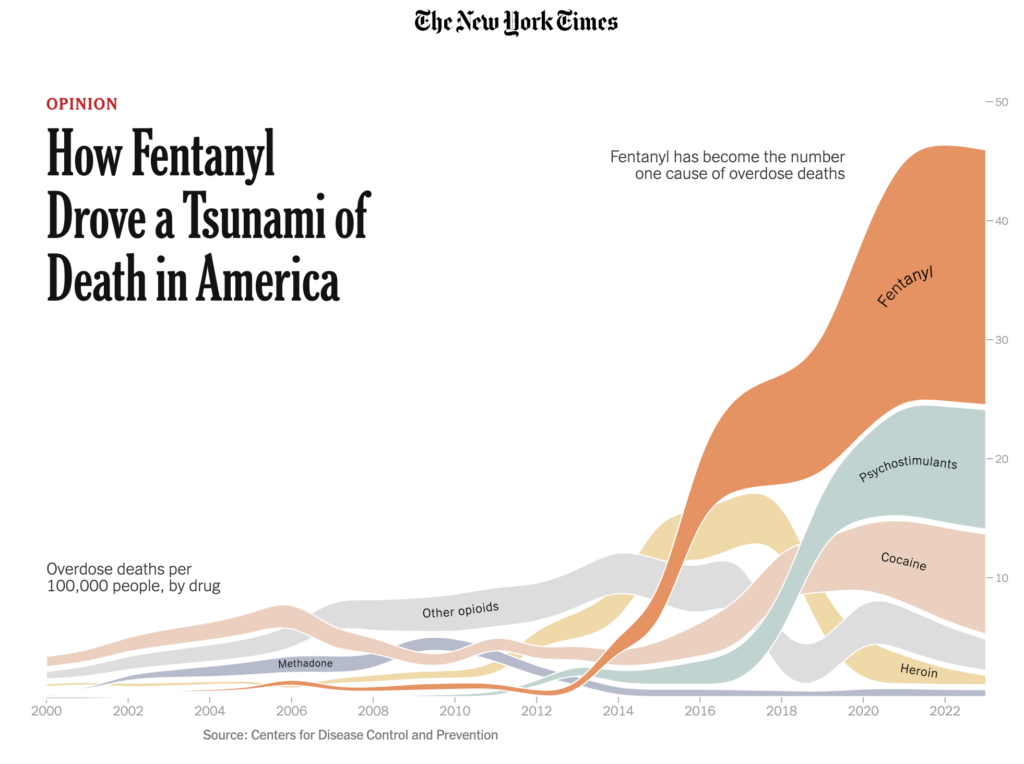

Last year over 70,000 Americans died from taking drug mixtures that contained fentanyl or other synthetic opioids. The good news is that recent data suggests a decline in overdose deaths, the first significant drop in decades. But this is not a uniform trend across the nation. To understand this disparity, it’s important to examine how we got here.

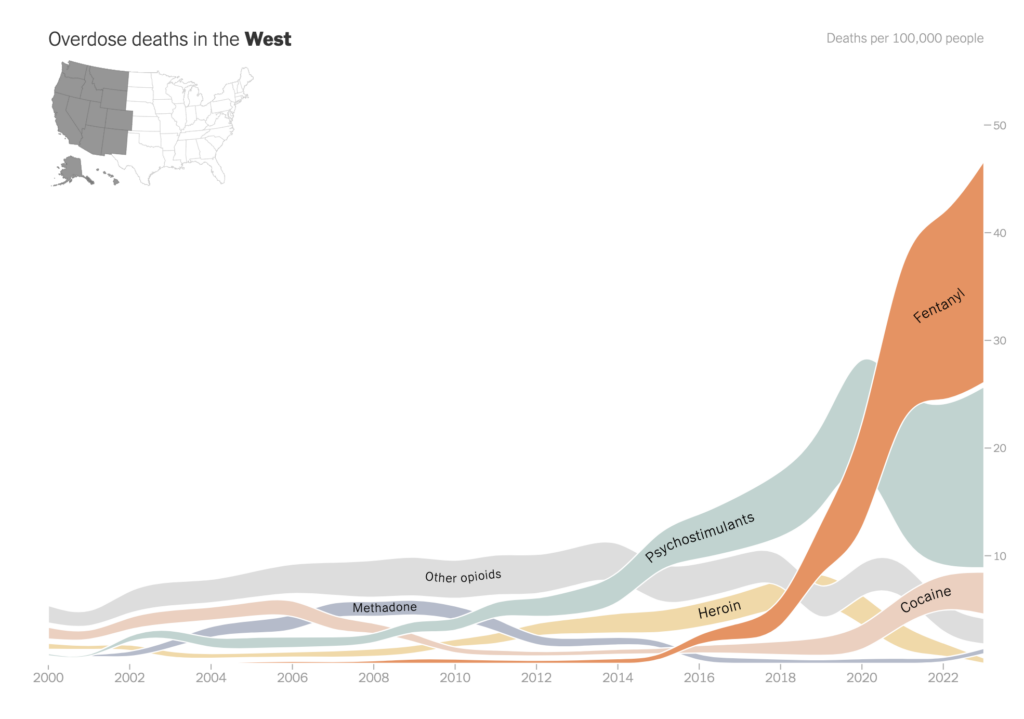

Today’s crisis is often described as a series of waves. But if you look at the data, it was more like a couple of breakers followed by a tsunami. First, prescription opioid fatalities rose. Then heroin deaths surged. And finally, illicitly manufactured fentanyl overtook all that preceded it.

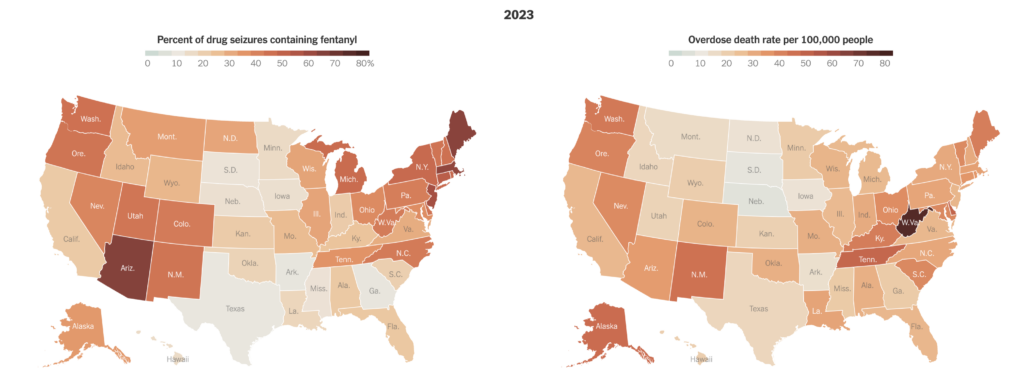

Once fentanyl and other synthetic opioids dominate a market, whether a state is red or blue doesn’t matter. Skyrocketing overdose deaths are nearly unavoidable, regardless of whether a state enforces tough penalties for drug possession or decriminalizes it.

Understanding how fentanyl saturated the drug supply, moving from the East Coast of the United States to the West, is critical to ending the worst drug crisis in American history.

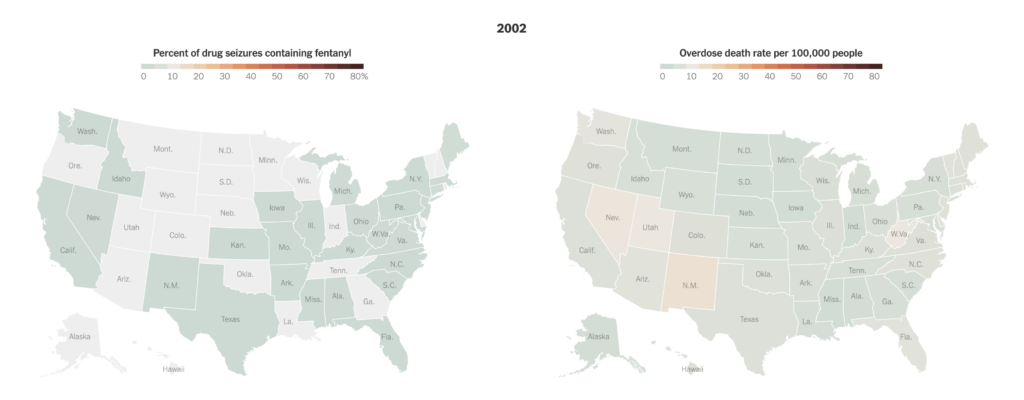

In 2000, America was in its first wave of the opioid crisis. This was dominated by deaths from prescription painkillers like OxyContin. As you can see in the first map, though not entirely new to the country, illicitly manufactured fentanyl made up a tiny percentage of total drug seizures nationwide.

Because escalations in opioid prescribing to treat pain were seen as the cause of the overdose problem, doctors began cutting off patients and law enforcement shuttered so-called pill mills. The number of opioid prescriptions began plummeting.

But little was done to offer alternative treatments for pain, or to help people addicted to opioids. This helped spur the heroin wave of the crisis, which started around 2011.

Then came the tsunami. By 2013, drug cartels had realized that they could slash their labor, manufacturing and transit costs by replacing heroin derived from farm-grown opium with a powder made in a lab — fentanyl.

Illegally manufactured fentanyl and similar synthetic drugs spread across the United States over several years, starting in the East and gradually moving to the West.

Before 2018, 80 percent of all deaths associated with fentanyl occurred east of the Mississippi. Now it dominates American drug markets. Since 2021, at least two-thirds of America’s 100,000 annual overdose deaths involved a synthetic opioid like fentanyl.

People who use drugs and those who work with them can often cite a specific month, sometimes a particular day, when fentanyl entered the local drug supply. It’s as if bartenders suddenly replaced light beer with a drink that tasted the same but was 95 percent alcohol and customers unwittingly chugged it. Many drinkers would rapidly pass out, and some might die.

When fentanyl arrives in a community, local responders go from dealing with, say, a few overdoses a week or a month to half a dozen or more per day.

Once a drug market is saturated by synthetic opioids, the death rate skyrockets immediately. That’s because they are much stronger: For example, fentanyl itself is 50 times more potent than heroin and another synthetic, carfentanil, is 5,000 times stronger.

This explains why after these synthetics enter a market, a large spike in deaths will happen regardless of whether the state has felony-level penalties for personal drug possession, like Texas and Idaho do, or whether it is experimenting with decriminalization, as Oregon did for a few years. Synthetic opioids hit Oregon and its neighbors at roughly the same time — but nearby states that didn’t decriminalize still saw deaths skyrocket. Historically, longer jail or prison sentences and higher arrest rates at the state or country level have not reduced opioid use or overdose death rates.

Preliminary data from the C.D.C. shows that between April 2023 and April 2024, the United States experienced its first national decline in overdose deaths in decades — the rate fell by 10 percent. But this good news hides regional variation. Some states in the West, where fentanyl generally arrived later, are still seeing sharp increases.

Heroin has historically been associated with cities, and New York City as the nation’s capital of distribution and use. However, increased opioid prescriptions — followed by sharp reductions — resulted in new heroin users in rural areas. Illegally manufactured fentanyl began appearing in both urban and rural drug markets in the East Coast.

Before illegally manufactured fentanyl took off across the country, Chicago got a brief taste of its power in 2005 and 2006, experiencing a spike of over 300 deaths. For unknown reasons, these drugs then disappeared and deaths did not rise dramatically again until 2014, when the drugs washed over the whole region.

Rural West Virginia and other Appalachian regions were the center of the earliest prescription opioid wave of the crisis, which led to the establishment of new heroin markets in places facing job loss. When pill mills in Florida that provided much of the region’s supply were closed, heroin, and then fentanyl, moved in.

One potential reason fentanyl spread more slowly to the West Coast is that heroin there has long been sold in a dark, sticky form known as black tar. In the East, heroin was sold as a light-colored powder, so it was easier to conceal fentanyl’s presence. Nonetheless, synthetic opioids have now spread fully to the West, in black tar and powder form and pressed into counterfeit prescription pills.

Combating this problem is deeply challenging, for several reasons.

Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are much cheaper and easier to make than heroin. To produce heroin, cartels need many acres of suitable land to grow poppies, hundreds of farmers and laborers to plant and harvest them, dozens of small, secure processing plants to turn raw opium into heroin, numerous guards and enforcers for protection and smugglers to get the product into the United States. To produce fentanyl, they need a few chemists in a lab, some commercially available substances and some distributors; it is often simply sent through the mail.

The amount needed to provide everyone in the United States who uses fentanyl with a year’s supply would require only a single trailer truckload of pure drug. To deliver the same amount for heroin would require six trailer truckloads. Consider that the U.S.-Mexico border is crossed daily by some 20,000 trucks, 200,000 cars, 100,000 pedestrians and a huge number of flights, trains and boats. The difference in the size and weight of fentanyl, compared to heroin, makes significantly interrupting the supply at the border nearly impossible.

So, what can be done?

The answer is to focus on the drivers of demand, not supply. This means addressing the roots of addiction and treating it compassionately. Addiction is most often an attempt to escape despair. The condition itself is defined by compulsive drug use despite negative consequences, which is why threats of punishment or even death rarely yield recovery.

We have a great generic opioid overdose antidote, naloxone. It needs to be cheaper and available everywhere, not hidden behind pharmacy counters but placed near every defibrillator and in every first aid kit. Two medications — methadone and buprenorphine — have proved to cut the risk of death among people with opioid addictions by 50 percent or more when used long-term. They also need to be made accessible to all people with opioid addiction. Right now, most rehabs still fail to adequately provide them.

Most addiction results from attempts to self-medicate isolation, social disconnection, psychiatric disorders, trauma and severe economic distress. It’s not coincidental that the exponential rise in overdose deaths has occurred in tandem with a profound increase in income inequality. Punishing people for trying to feel better in a world that doesn’t seem to want them doesn’t help.